hey’all. on this awful anniversary, i’m publishing an essay i’ve written over the past several weeks. it includes some heavy stuff and might press on your tender points. thanks for being with me in a longer read about the way disability justice points to solidarity with Palestine.

-kg

In a forest full of queers, Ann-Archy Artist’s head is piercing a beat-up American flag. It’s covered in blood. So is she. Beyoncé sings.

Mercy on me, baby

Have mercy on me

Tonight, honey, my LSD is doing some thinking. Did she choose to carry that flag? Is she stuck with it?

Hurtin’ badly

I can see you’re hurtin’ badly

She moves quickly within the crowd that has formed. There’s a message coming and it’s urgent.

Trumpets blare with silent sound

I need to make you proud

She lifts the flag off her body, splitting the fabric down the middle with a sound that is satisfying in the register of bubble-wrap.

Them old ideas (yeah)

Are buried here (yeah)

She throws it onto the ground into a burial pit lined with candles.

The end of "AMEN" (the final song on COWBOY CARTER) is a big, buzzing swell.

The final sound is a traveling ding, like a stratospheric escape.

"AMERICAN REQUIEM" (the album’s first song) begins.

She remembers something infuriating as she lights a cigarette with one of the candles.

For things to stay the same, they have to change again

She bends over slightly and starts to pull something out of her ass. Another American flag. It wasn’t just on her, it was in her.1 It too is going in the ground.

It's a lot of talkin' goin' on

While I sing my song

She is using one crutch for this performance. She darts around the dirt and stage with it. One moment the crutch is just there near her, the next it’s waving overhead.

Looka there, looka there, now

Looka there, looka there

She points to people in the audience holding other flags. Congo, Sudan, Ukraine, Palestine.

Can we stand for something?

Now is the time to face the wind

She attaches the Palestinian flag to her crutch and waves it over the audience.

Goodbye to what has been

In a video by Glamour Cadaver, Artist is waving the crutch and flag, brightly lit, outside, surrounded by the crowd.

Standing next to the DJ booth at the end of the performance, I am sobbing. A chant erupts: “FREE, FREE PALESTINE!” Then I’m crouching in the dark woods with my notebook and pen.

Ann Artist’s performance was a powerful declaration of interdependence of the united states of disability justice and global solidarity for decolonization. Lemme explain.

This was Honcho Campout 2024, described by its organizers as “a queer gathering in nature that celebrates those doing the heavy lifting in their local scenes.” It takes place at an inter-faith sanctuary on the unceded land of Shawnee and Massawomeck peoples. It’s difficult to explain what kind of magic happens there, but the artist and scholar DJ Voices gets at it by invoking Mircea Eliade’s 1963 insights into modern ritual behavior: “a constant b2b between the sacred and the profane.”

At Honcho, you’re basking in the too-much-ness of the explosion of artistic forms around you: the DJing of course and the performance artistry, but also the beauty of the super solid rigging around the dance floors, the dancers and their gaggy or other-worldly outfits, fabrics hung over paths and the creek, the food, the elixirs, the medics and trip sitters and safety team, the handmade pendant hanging over someone’s tent that says “VERY DEMURE.” It’s sacred.

At Honcho, your snot rockets are brown. You’re doing a bit too much K because you can’t really see in the dark and then you’re nauseous in slow motion, hoping a friend will materialize out of the darkness. You’re waiting in line for a flushing toilet except one determined bottom didn’t eat enough fiber and has been douching for 40 minutes. It’s profane.

And the b2b of it all that produces a full throttle “bursting kaleidoscopic reality,” per DJ-scholar-writer Joe Delon’s gorgeous 2024 reflection. Honcho Campout is a place of little revelations everywhere. It can feel like you’re thinking not just with your whole body, but with your whole body’s whole ecology, with others, even when you also feel somehow alone, when tough lessons crash through the veil of pleasure.2

And here’s where it gets really close to the bone: in this difficult place, far from a paved road, where we stay up past sunrise and weaken our immune systems and do drugs and damage our hearing, some of us are getting the best healthcare we’ve ever known.

As a prop, the crutch is too meaning-full. Disabled people’s mobility devices are often staged as ableist proxies for weakness, impotence, or loss so that something can be done about an evil. The crutch, the brace, and wheelchair… they often disappear, either because something has been miraculously fixed or a disabled person has been killed. The crutch is an ableist crutch. (See it even in idiom?)3

But Ann Artist’s crutch wasn’t a prop. About a month earlier, she was performing to “SWEET ★ HONEY ★ BUCKIIN’” when she landed a jump from the bar onto a previously unknown hairline fracture in her leg. Buoyed by adrenaline, she continued her lipsync, dueting with a visibly broken bone. She was carried out on a stretcher in the same elevator where Solange fought Jay-Z. That performance shaped this one, with metal (a titanium rod in her leg and an aluminum crutch in her armpit).

The crutch began as a way to meet the performer’s access need. But when it waved the Palestinian flag, it soared into metaphor, representing what scholar Jasbir Puar has called “debility”: the slow violence enacted upon entire populations that goes unchecked by rights-based movements that produce disability as an identity, something one could be proud of. Debility reveals, instead, a global distribution of who is made available for injury and death.

That hyper-legible crutch is the explicit intention of Israeli state violence. Following the 2018 - 2019 Great March of Return that mobilized tens of thousands of Gazans in protest, a U.N. report found that 81% of Israeli gunshots on demonstrators were aimed at their legs. “In the span of just a year and a half (March 2018-September 2019), there were over 6,500 limb injuries, with at least 1,200 becoming amputees who need limb reconstruction,” according to Disability Under Siege.

In March 2024, CNN’s Nima Elbagir reported from inside a warehouse where aluminum crutches and manual wheelchairs for Gaza were rejected or held in a long wait for clearance by Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT). International humanitarian law (the unimpeded passage of aid and protection of the wounded) hasn’t dampened Israel’s success in turning civilians into combatants and essential medical supplies into possible threats. This makes accessibility itself part of the pretext for genocide.

The creation and maintenance of Gaza as the world’s largest open-air prison - formally declared “unliveable” long before October 7, 2023 - would not be possible without the $310 billion the U.S. has given Israel since its founding. And then there’s the technical assistance and knowledge that doesn’t have a dollar figure. A 2018 Deadly Exchange report catalogued the techniques of mass incarceration and disablement that are shared in law enforcement exchange programs between the U.S. and Israel.

This is how the connections between disability justice and Palestinian liberation are direct. As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha wrote on the 100th day of the current siege of Gaza, “Disability justice was founded by a bunch of revolutionary disabled people, mostly BIPOC, who had been involved in radical movements against imperialism and racism for all their lives. We created disability justice out of our lived disabled experiences with war, occupation and genocide.”

While Israel’s violence is literally fueled by the American defense industry, the U.S. is systematically disinvesting in its own communities, “specifically impacting disabled, deaf and neurodivergent negatively racialized communities,” as the Abolition and Disability Justice Coalition wrote in its 2021 “Statement of Solidarity with Palestine.”

Since May 2023, 25.2 million people have been thrown off Medicaid in the U.S., the only insurance that covers disabled people’s significant medical expenses like powerchairs and 24/7 attendant care. And in August 2024, Congress cut funding for the program that ensures uninsured and underinsured people can access Covid vaccines for free.

Yet there’s money for Israel’s “bunker busters” dropped on children in tents. There’s money for the decimation of Palestine’s agriculture, the land’s regeneration of life. There’s money for Israel to harvest sperm from the bodies of its dead soldiers.

When Ann Artist raised that aluminum crutch in the air, the same kind of crutch that Palestinians desperately need right now, she collapsed the abstractions that vex how we talk about Palestine. When she buried the American flag and then flew the Palestinian one, she called our attention to Israeli terror as the ableism of U.S. imperialism in extremis.

“I was supposed to break my leg and do this number,” Ann Artist tells me when I talk with her after we’re back home. I ask her if the performance could be understood as a comment on the working conditions of Honcho. No, she says, “the working conditions were perfect.”

That’s because the conditions of the performance - the broken leg, the crutch, the flags, the dirt - were crucial alchemical elements of the message the performance conveyed: perfect health is an impossibility in a country whose civic religion is the exchange of precarity at home for genocide abroad.

Ann Artist’s Honcho performance was curated by Charlene Incarnate, an enduring legend of NYC performance artistry who ascended into drag excellence during Brooklyn’s “drag renaissance” in the early 2010s. Charlene is an artist who transforms herself on stage. She’s known for her performances of castration to Britney’s “‘Til It’s Gone” and live, on-stage hormone injections. Something is materially different by the end of her most numinous numbers.

Ann Artist’s flag burial/cathexis is part of Charlene’s quiet emergence as a curatorial powerhouse.4 Charlene, like Ann Artist, came down hard during a 2017 performance in a temple in the woods. She broke her wrist. And she, too, did not - or could not - stop performing.

This coincidence is really a shared commitment to performance as ritual, where what happens is tantalizingly immediate. Drag artistry as ritual means what happens on stage really happens, that symbolic uncertainty is condensed into object form.

In the middle of Ann Artist’s performance, in the lull between “AMEN” and “AMERICAN REQUIEM,” Charlene came on the mic to indicate that the number wasn’t over. “Let the woman speak!” she said. But Ann Artist never spoke, really. We never heard her voice, she never used a microphone. The ritual spoke for itself, with exquisite loyalty to Beyoncé’s frustrations (“It’s a lot of talkin’ goin’ on… Can we stand for somethin’?”).

We could take the bait here and think about the performance in terms of “free speech,” since the “desecration” of the American flag is at the heart of some of the most potent first amendment jurisprudence of the 20th century.5 That we’re also talking about drag here, an art form in the crosshairs of the current assault on gender expression and trans healthcare, makes it even more tempting.6

But that’s a false flag and we know it in our bodies. The context around “free speech” collapses when the spread of mask bans encloses and constrains anti-imperialist direct action work, using disabled people as pawns in ableist control of space. “Free speech” is a deck chair on the Titanic when public life itself is inaccessible and unsafe for disabled, chronically ill, and immunocompromised people.

The magic - and I do mean magic - of Ann Artist’s performance is that it pointed to escape from what makes political speech feel so cheap in the months before a presidential election. It pointed to something we can feel and know to be true.

After Honcho, disabled artist Mae Howard sent me a beautiful reflection on access through their experience at the vigil for Palestine on the final afternoon of the festival:

Surrounded by new friends, collaborators, and beloved kin, we wept while laying amidst the open sky and field. We were held by each other, by the desire to gather, by the yearning to pause amidst the joy that we had all been brought into over the weekend. I am grateful to have been held by that pause and the intimacy of grief that was held by our small collective group.

The ability to tap into the grief of this collective moment, even anger of why it has taken so long for so many of us to have access to this now foundational space of queer utopia, is something that to me is as important as the joy that Honcho offers to its attendees as well.

The ritual’s the thing. The vigil was one of several solidarity actions at the festival. There was also an anti-zionist Shabbat prayer, Sarah Shulman and Dorgham Abusalim’s talk about effective action for Palestine, the shirt Deezy wore during their set (“Queer as in Free Palestine”), the flags that waved behind ASL Princess in her surprise b2b with St. Mozelle, whose vibe alchemy beautifully transmuted the intensities of Ann Artist’s performance (especially the genius selection of SCRAAATCH’s “Don’t Talk to Me” that continued our collective search for whatever’s on the other side of empty political blathering.)

One evening at Honcho, historian Nikita Shepard shared some of their research about the many ways queers have lived in the woods. The Radical Faeries, the Land Dyke movement, the Stonewall Colony, and many other communities have organized outside of cities for decades. Looking across these wild histories, Nikita shared one of those elegant truths that helps you explain yourself to yourself: the most common thing is that they - we - gather for short periods of times in the woods.

What we do in the woods is stronger than the scramble for a perfectly shared political analysis that never seems to arrive for us to do something together. We share the sanctity of queer space. We put tarps over stuff when it rains. We leave notes for others about clever workarounds when things break. We pick things up. We put things down. And some things we bury.

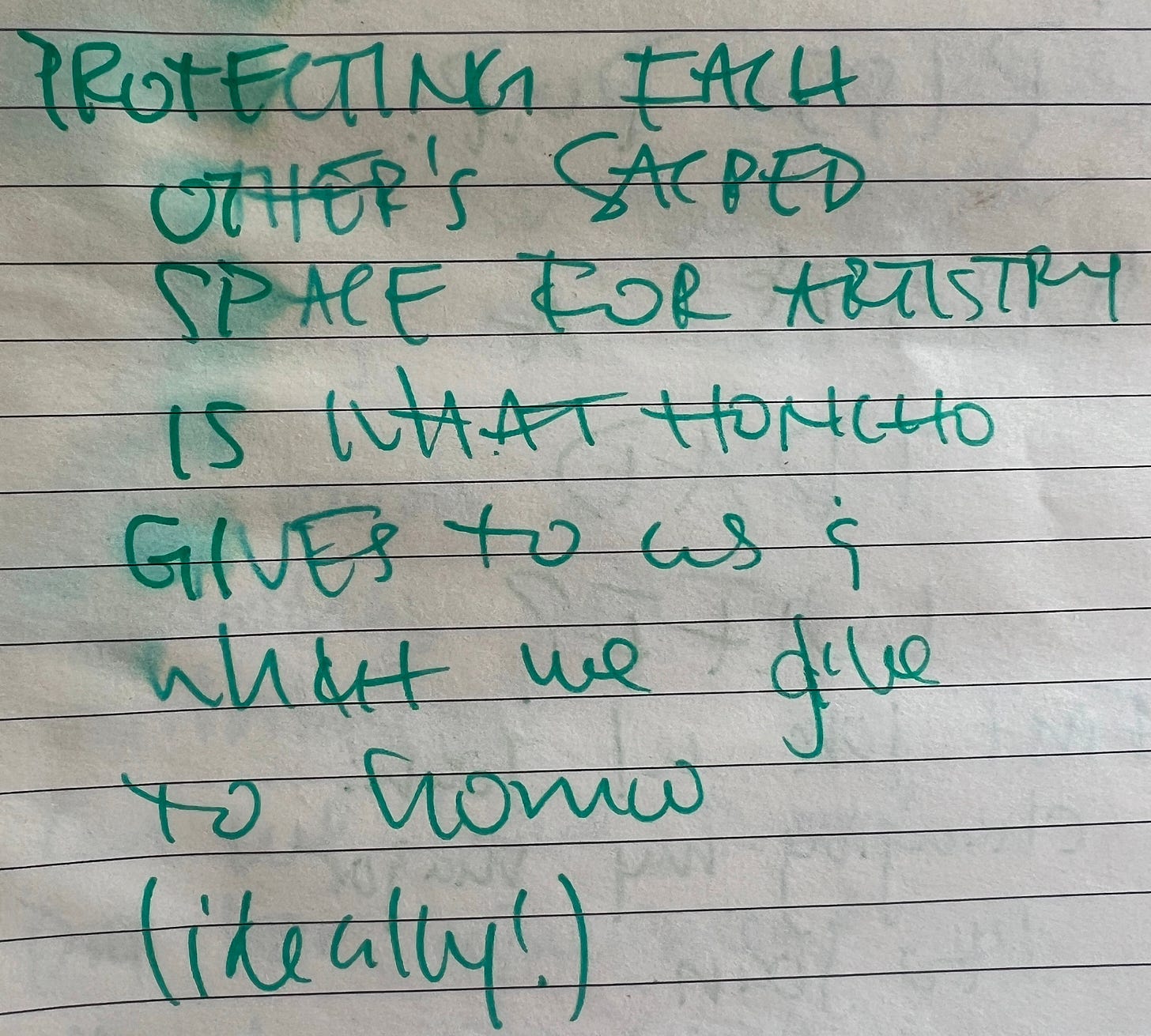

I want to call this magic and mean it. It’s the sacred b2b with the profane. It’s what helps me know that disability justice means a free Palestine. It’s what helps me understand what I meant when I took down one of the shortest notes of my time at Campout:

“honcho catchphrase: god tore”

This part of the performance makes me think of an inaugural text in queer theory, Leo Bersani’s 1987 essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?” As the AIDS epidemic seem to confer a biological truth to heterosexist views of anal sex as intrinsically dangerous, Bersani saw a more radical extrapolation from this association. What really could each person lay to rest within their own body? What if sex could kill misogyny? I love that Ann Artist could be finally taking up Bersani’s question, performing the death of patriotic allegiance to death itself. The rectum is a grave and here lies the idea of America.

I love how LeeLee James, an icon on the Honcho dance floors, has described therapeutic solo time outdoors as “the Twirl” that forms “the love language I use with myself, a check-in between self and universe.” At Honcho, it’s a together twirl.

There are notable exceptions to this trope when disabled people call the shots. Clark Matthews and Mia Gimp’s 2013 short film “Krutch,” for example, figures libidinal prothesis into an often-ignored disabled sexuality.

At Honcho ‘24, we danced with the absent presence of someone we love very much, someone who is currently lost to us. Char and I met R. 17 years ago, each of us such different people then. R. led a ritual integration of a Tennesee sanctuary’s autonomous zones as we gathered for the first time in the Covid era. She was the one who handed the curator role to Char for Honcho ‘24. Char knew what might be coming, politely telling me over drinks in my backyard once that my inviting others to ask ourselves if “we have what they need” is a fool’s errand when someone is having a major break. When we talked about R. at Campout this year, I asked Char how she knew what to do as the new drag curator. “I ran each artist through her filter,” she said, smiling at the unshakeable memory of R. before the trouble. The hidden hurt is what makes Charlene’s most recent professional transformation as a curator so necessarily quiet, but no less profound. Here in the quiet edges of this essay, we say: R., we love you. None of us can even imagine yet how good it will feel to celebrate your return.

I know something about this because the person who advised my doctoral dissertation, Dr. Carolyn Marvin, burned a flag at the University of Pennsylvania in 1989. She did it as a class exercise, saying nothing while she brought a flame to the flag she had soaked in lighter fluid. Months earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that flag burning was constitutional because it accompanied protest speech. Marvin wanted her students to contemplate if the act alone can be speech.

It sparked a national outrage. The Pennsylvania legislature passed an official censure of her teaching. She received death threats. She got a German Shepard. And in her resulting book, Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Totem Rituals and the American Flag, she makes sense of the furore as a civic religion of American patriotism, organized around its sacred flag, “whose followers engage in periodic blood sacrifice of their own children to unify the group.” The flag, she would say, is bloody but very much alive as a representation of the bleeding bodies of young soldiers killed at war.

Ann Artist asks: “…and if it weren’t alive?”

We’re back again at the social regeneration of what hurts us. Some of the most important theory about gender is also predicated on the relationships between speech and body, notably Judith Butler’s extension of “speech acts” and nonverbal communication into the realm of everyday performativity. But now, it seems the right has taken this up only so well to weaponize it against queer and trans people, making drag queen story hours and access to gender affirming care a crisis on the level of the constitution of the whole child.